This month’s events in El Paso, the presidency of Donald Trump, the realignment of American political parties over the past fifty years – indeed the totality of American history itself on this, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first documented black slave on our shores – can be summarized by one powerful letter:

This month’s events in El Paso, the presidency of Donald Trump, the realignment of American political parties over the past fifty years – indeed the totality of American history itself on this, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first documented black slave on our shores – can be summarized by one powerful letter:

W.

Mariana Chmielowicz was born and raised in the kingdom of Galicia in the late 19th century.Galicia was the poorest region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an amalgam of Poles and Slavs in the middle of what would soon become Europe’s bloodiest battleground.

Whether through good luck, ingenuity or a little of both, Mariana joined thousands of Galicians in emigrating first to Germany then by ship to New York City. She left the day after Valentine’s Day, 1902, with $12 in her pocket and, for the Anglophones of her new home, an unspellable, unpronounceable Polish name. The clerk recording her entry beneath the shadow of the Statue of Liberty on March 1 noted her simply as “Chmiel, Maria.”

She told immigration officials she was joining a cousin at a labor farm in Priceburg, a suburb of Scranton in eastern Pennsylvania whose name would soon be changed to Dickson City.

By 1910, Mariana had met and married Josef Matan, a fellow Polish migrant, who had been born on the western edge of Russia – a couple in the

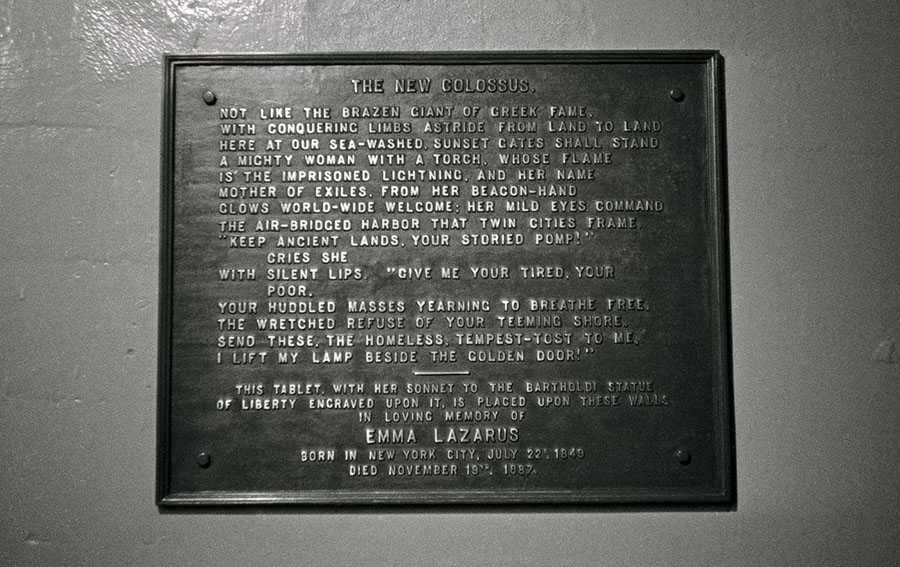

closing years of the long 19th century fleeing the convulsive final decades of European empires soon to vanish in flame and blood, entering through the golden door beside which the Mother of Exiles lifted her lamp.

“Matan” was a shorter name, but apparently no easier for English speakers to spell correctly. The growing family – three living children by the time Census taker Joseph Eisenberg knocked on their door across the railroad tracks from the Lackawanna River in the working-class Scranton suburbs – was spelled “Matta,” “Maden” and “Maton” on official documents for decades.

But regardless of misspellings, the Matan family received something far more valuable from Eisenberg on April 26, 1910: under the column marked “Race,” he scratched the letter W.

No matter their language (they couldn’t read or write English yet), no matter their birthplace (European backwaters), no matter their nationality (nonexistent at the time), the Matans had the W.